They drew aside as he passed down the village, and when he had gone by, young humorists would up with coat-collars and down with hat-brims, and go pacing nervously after him in imitation of his occult bearing. There was a song popular at that time called the “Bogey Man”; Miss Statchell sang it at the schoolroom concert (in aid of the church lamps), and thereafter whenever one or two of the villagers were gathered together and the stranger appeared, a bar or so of this tune, more or less sharp or flat, was whistled in the midst of them. Also belated little children would call “Bogey Man!” after him, and make off tremulously elated.

Cuss went straight up the village to Bunting the vicar. “Am I mad?” Cuss began abruptly, as he entered the shabby little study. “Do I look like an insane person?” “What’s happened?” said the vicar, putting the ammonite on the loose sheets of his forthcoming sermon. “That chap at the inn—“ “Well?” “Give me something to drink,” said Cuss, and he sat down. When his nerves had been steadied by a glass of cheap sherry—the only drink the good vicar had available—he told him of the interview he had just had. “Went in,” he gasped, “and began to demand a subscription for that Nurse Fund. He’d stuck his hands in his pockets as I came in, and he sat down lumpily in his chair. Sniffed. I told him I’d heard he took an interest in scientific things. He said yes. Sniffed again. Kept on sniffing all the time; evidently recently caught an infernal cold. No wonder, wrapped up like that! I developed the nurse idea, and all the while kept my eyes open. Bottles—chemicals—everywhere. Balance, test-tubes in stands, and a smell of—evening primrose. Would he subscribe? Said he’d consider it. Asked him, point-blank, was he researching. Said he was. A long research? Got quite cross. ‘A damnable long research,’ said he, blowing the cork out, so to speak. ‘Oh,’ said I. And out came the grievance. The man was just on the boil, and my question boiled him over. He had been given a prescription, most valuable prescription—what for he wouldn’t say. Was it medical? ‘Damn you! What are you fishing after?’ I apologised. Dignified sniff and cough. He resumed. He’d read it. Five ingredients. Put it down; turned his head. Draught of air from window lifted the paper. Swish, rustle. He was working in a room with an open fireplace, he said. Saw a flicker, and there was the prescription burning and lifting chimneyward. Rushed towards it just as it whisked up chimney.

So! Just at that point, to illustrate his story, out came his arm.” “Well?” “No hand—just an empty sleeve. Lord! I thought, that’s a deformity! Got a cork arm, I suppose, and has taken it off. Then, I thought, there’s something odd in that. What the devil keeps that sleeve up and open, if there’s nothing in it? There was nothing in it, I tell you. Nothing down it, right down to the joint. I could see right down it to the elbow, and there was a glimmer of light shining through a tear of the cloth. ‘Good God!’ I said. Then he stopped. Stared at me with those black goggles of his, and then at his sleeve.” ‘’Well?” “That’s all. He never said a word; just glared, and put his sleeve back in his pocket quickly. Mr. Bunting thought it over. He looked suspiciously at Cuss. “It’s a most remarkable story,” he said. He looked very wise and grave indeed. “It’s really,” said Mr. Bunting with judicial emphasis, “a most remarkable story.”

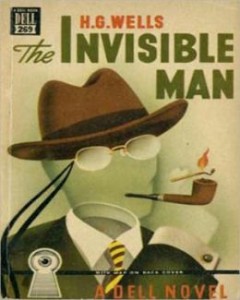

H.G. Wells

The Invisible Man, 1897